| Home Register Puzzles Solve Teams Statistics Rules Solving Guide F.A.Q. Archive mezzacotta |

Solution: 5E. Cleaving Hearts

The challenge of this puzzle is to deduce enough of the rules of the card game Cleaving Hearts to assign points correctly to the winners of each trick. Most — although not all— of the rules of this game (which was invented for this puzzle) can be deduced from the example game fragment that forms the puzzle. Here are the rules in full:

- Objective: Cleaving Hearts is an eight-player variant of the trick-taking game Hearts. Each heart card is worth one point and each queen of spades is worth thirteen points. The game is played over multiple rounds until at least one player has scored 100 points or more. The player(s) with the fewest points win.

- Decks: Two standard packs of playing cards are used. Remove the Jokers, and shuffle the remaining 104 cards together.

- The Deal: At the start of each round, deal out thirteen cards to each of the eight players.

- The Pass: In the first round, before play begins, each player selects three cards and passes them to their left. In subsequent rounds, three cards are passed to the next player along, and so forth.

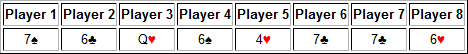

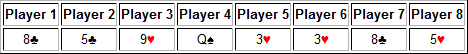

- Initial Lead: The player(s) who hold the two of clubs begin the first trick by leading this card. If one player holds both twos of clubs, that player only leads one of them in the first trick. If two different players each hold the two of clubs then they lead those cards simultaneously.

- Single Lead:

In a trick, if only one card is led, play proceeds around the table

sequentially, and each subsequent player must follow the suit of the

card that was led if possible.

For example, in the following trick play proceeds in the order

1→2→3→4→5→6→7→8.

- Multiple Leads are Simultaneous:

If two or more cards were led then those cards are revealed simultaneously,

and subsequent players follow sequentially, revealing their cards

simultaneously where possible.

They must follow one of the suits that were led, unless they have no

cards remaining in any of the suits that were led.

For example, in the following trick, players 1 and 7 lead with a seven of spades and a seven of clubs, respectively. Those who next simultaneously reveal their choices are players 2 and 8. Since the next player after player 8 is player 1, who has already played, that branch is exhausted and play proceeds non-simultaneously from player 3 onward. The play order can be represented thus: (1,7)→(2,8)→3→4→5→6.

Note that player 2 chose to follow player 7's lead, as there was no obligation to follow player 1's suit. Also note that, in this example, players 3, 5, and 8 do not follow either of the suits that were led, and hence it can be deduced that none of these players have any remaining spades or clubs. - Restriction on Leading Hearts: Hearts may not be led unless and until one of two situations occur: Either a player who must now lead has only hearts remaining in hand; or else someone discarded a heart in a previous trick as a result of not being able to follow whichever suit(s) were led. Hearts are said to be broken after either of these situations has occurred in a round, and every player is then allowed to lead hearts.

- Single Winner of a Trick:

A player wins a trick if that player plays the highest ranked card

amongst all those who followed the suit(s) that were led.

In this situation, all of the scoring cards are won by the single

winner.

The winner leads to the next trick in the round.

For example, in the following trick where player 1 led the five of spades, player 2 wins the trick with the queen of spades even though there are higher ranked cards in the trick, because those other cards were not following the suit that was led. Player 2 takes all scoring cards (five hearts and the queen of spades) and scores eighteen points. Player 2 leads to the next trick, if any.

In the next example, where both hearts and clubs were led, the single winner is player 3, who wins due to having played the highest ranked card (the nine of hearts) in either of the suits led. Player 3 takes all scoring cards (four hearts and the queen of spades) for seventeen points, and will lead to the next trick.

- Multiple Winners of a Trick:

Two or more players can win a trick by playing the equal highest

ranked card following the suit(s) that were led, and scoring cards

are divided evenly between winners where possible.

Winners lead to the next trick simultaneously.

For example, in the following trick where player 4 led the five of diamonds, players 1 and 7 will tie on the highest card following suit (the six of diamonds). Since there are two scoring cards (the six and jack of hearts) and two winners, each winner takes one of those cards to add to their score pile. Players 1 and 7 will choose and simultaneously lead cards for the next trick.

- Jackpotting:

Because this is a card game, it is convenient to keep score during

a round with cards, rather than pencil and paper.

Accordingly, no fractional points are awarded, and trick totals are

shared only to the extent that distributing the point-scoring cards

fairly is possible.

Scoring cards must be divided fairly amongst winners of a trick.

Cards that cannot be fairly assigned cannot be split between

players.

If there is no fair way to distribute a trick's point-scoring cards

between multiple winners then excess points are not assigned and

the cards representing those points jackpot to the next trick.

In the example below, player 5 led the six of diamonds, and the trick was won by players 1 and 4 who both played the jack of diamonds. They cannot share the single point-scoring card (the jack of hearts), so that card jackpots to the next trick.

In this further example, a single queen of spades (worth thirteen points) has been played, but there are two winners of the trick (players 7 and 8, who both played the ace of spades). Since the queen of spades card cannot be given to both players, it is given to neither and instead jackpots to the next trick.

Here are two other instances where jackpotting would occur: If a trick won by two players included a heart and a queen of spades, which totals fourteen points, no points would be given to the winners because it is impossible to fairly distribute those cards. Both cards would jackpot to the next trick. If the point-scoring cards of the trick were instead three hearts, two of those cards would be awarded (one to each player), and the remaining heart would jackpot to the next trick. - No Jackpot at Round's End:

If there are any unawarded cards after the final trick of a round,

those cards do not jackpot to the next round.

They are simply not scored and reshuffled back in with the rest

of the cards for the next round.

In the example below, if spades and clubs were led in the final trick of the round, then there would be four winners but only two point-scoring cards. A fair division is not possible (assuming that no cards have jackpotted from the previous round), so those points are not scored by anyone.

- Shooting the Moon: In a single round, if only one player scores any points then those points score negative instead. Note that due to the jackpotting rules this player may score fewer than 52 points (prior to the negation).

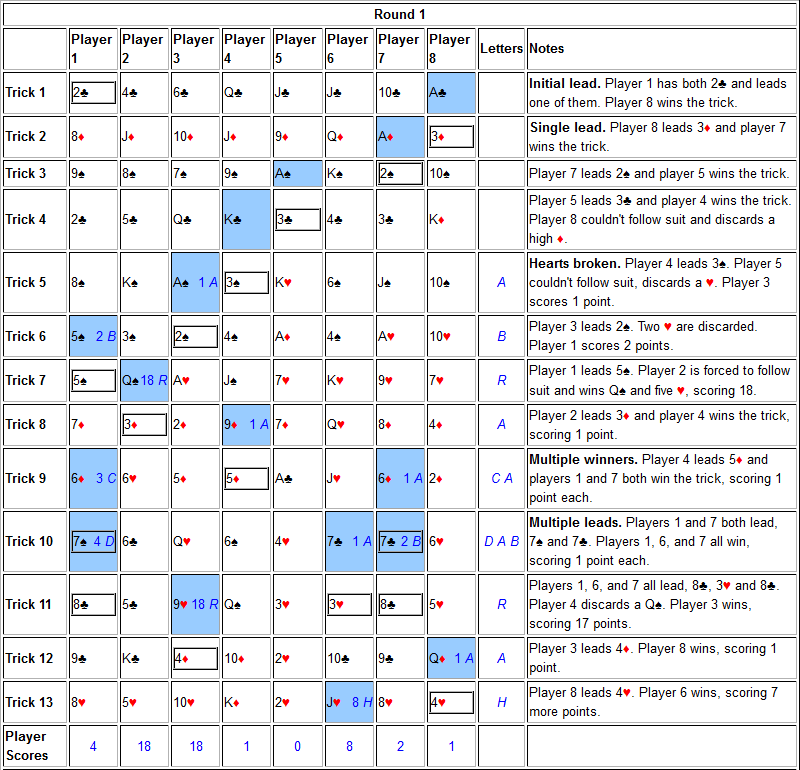

A key observation in this puzzle is that, as the game progresses, the scores of players can be used to spell words. (Realising this also helps clarify some uncertainties about the rules, and smooth over bits that are unclear.) Player 3 is the first to win one heart, achieving a score of one, which can be interpreted as the letter A. Player 1 then scores two hearts, achieving a score of two, which can be interpreted as the letter B. Following this process in round 1 results in the letters ABRACADABRAH. Note the H at the end.

It is the winner's scores that determines the letters. In some tricks there are multiple winners and multiple letters may be extracted from such tricks. In the first round, two winners produce the letters CA in trick 9 by scoring one point each, and then three winners produce DAB in trick 10, again by scoring one point each. These tricks should provide some insight into the rule of dividing point-scoring cards equally.

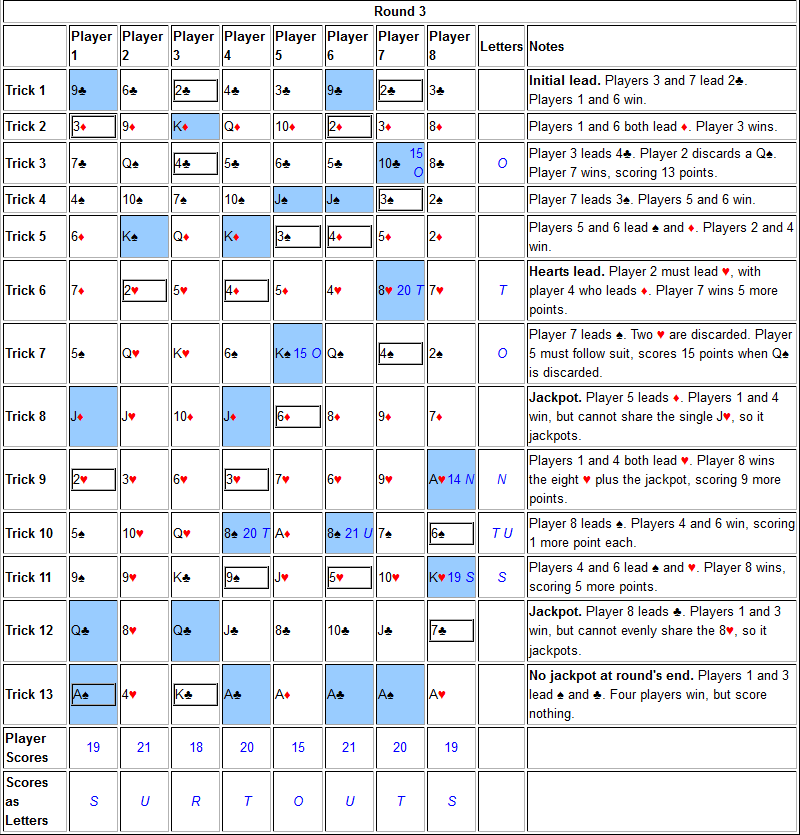

In round 2, the scores continue to increase, and the first letters obtained are OCU. These letters follow the H at the end of the first round, and it may be surmised that the word HOCUS is intended. However, the S is not so easy to extract. It is here, in tricks 8 and 9, that the jackpotting rule must be deduced to obtain an S. Doing so produces the full set of round 2 letters: OCUSPREST.

Round 3 produces the letter O (completing the word PRESTO) and this is followed by TONTUS. Jackpotting in tricks 12 and 13 produces no new letters, and the rule about not jackpotting in the final trick must be deduced to avoid changing the scores further. Note: TONTUS is an obscure "magical word", similar to ABRACADABRA, but none of these words are the solution to the puzzle. (The invaluable Cecil Adams provides details about the origins of these words.)

The full worked solution is below. Leads are outlined and winners have blue backgrounds. Running totals of player scores are written in blue, with the corresponding letters next to them.

In the end, the final scores are tallied and the corresponding letters can be read left to right, spelling the answer to this puzzle: SURTOUTS. (A surtout is a type of coat, which might feasibly be worn by some magicians.)

Author's Notes

Can a puzzle teach a game? Can a game also be a puzzle? I decided to find out. The central idea for this game was that there could be multiple winners of a trick, and hence the lead could become split. There would be a corresponding mechanism for merging back to fewer leads, by having fewer winners. This repeated splitting and merging of the lead was the source of the name Cleaving Hearts since in English 'to cleave' can mean to split but can also mean to join.

Although I've given many rules above, not all of them can be (or need be) deduced from the sample game. For instance, knowledge of The Pass is not explicitly required to solve the puzzle. It may be inferred from trick 5 of round 1 when player 2 plays a king of spades while there is still one card remaining to be played in the trick, tempting fate by potentially allowing the next player to drop a queen of spades. This hazard would be unlikely if player 2 had passed cards to player 3 before the first trick, and thus knows that no queen of spades was passed to them.

Similarly, the simultaneous nature of play when there are multiple leads might not be strictly required to solve the puzzle, but may nevertheless be inferred by observing how suits are followed and which players duck just under the currently winning cards. Trick 11 of Round 3 shows players 4 and 6 leading spades and hearts, and the subsequent players 5 and 7 both follow hearts, showing that player 5 is aware of player 6's lead and need not "follow from the left". A similar situation occurs in trick 4 of round 2, where players 6 and 8 lead, then players 7 and 1 go low, but once player 2 goes high the remaining players duck just under player 2's card. This illustrates what happens when two simultaneous branches reduce to a single line of play.

The rules concerning Shooting the Moon were given in the summary above, but no player attempts this in the puzzle, and it is not necessary to know this rule to solve the puzzle. The rule is stated for completeness. Whether a player had successfully or unsuccessfully attempted this goal, it would have required a different formulation of the puzzle, since a change of up to 52 points in score would not lend itself so easily to a direct alphabetic mapping from scores to words. So, unfortunately, this rule was not incorporated into the puzzle.

The Jackpot rules were perhaps the most difficult to discover. The embedded magical words were both a mechanism to cross-check the deduced rules and an aid to discover new rules. The puzzle was extensively reworked after initial test-solves, moving the first instance of a jackpot from trick 2 of round 2 down to trick 8, to coincide with the final letter of HOCUS.

The distribution of points in cases of multiple winners was another challenging aspect of this puzzle. The need to think in terms of scoring by physically handing cards to players was one of the intuitive leaps required to solve the puzzle. Many test-solvers considered multiple ways of dividing points between winners, particularly when a queen of spades was present in the trick. Again, the embedded magical words could be used to cross-check these options (or, in at least one test-solver's case, to bypass a full understanding of this process).

When constructing this puzzle, it was important to find words with letters that were small increments on earlier words (up to a difference of 8, formed using hearts cards), or else large increments (a difference of 13 or more, formed using a queen of spades plus one or more hearts cards). Abracadabra was an ideal first word, and had a suitable thematic link with magical tricks. If a difference in letters was between 9 and 12, this required jackpotting to spill some points over to a later trick. This occurs in tricks 8 and 9 of round 3. Jackpotting was also useful for eliminating some points at the end of round 3, to make it more difficult to reverse engineer the secret, which would otherwise simply be the sum of three rounds each containing 52 points.

During test solving, while the puzzle was being considered for day 3, an idea was floated of hand writing "How magical" under the puzzle to hint at Abracadabra and provide an easier way in. After some discussion, this was rejected as there was a need for truly hard puzzles for day 5.

Also during test solving, several solvers reinvented one of the rules of Cancellation Hearts, where equal highest ranked cards cancel each other out. That variant of Hearts also has a form of jackpotting since it is possible for an entire trick to become cancelled if there are multiple ties. The point-scoring cards would still count even if they are part of a tie, but in a jackpot situation they'd spill over to the next trick. Cancellation Hearts also removes a two of clubs in order to ensure a single lead for each trick, and the cancellation mechanism attempts to ensure a single winner, thus making the game quite similar to Hearts.

By constrast, Cleaving Hearts embraces the notions of multiple leads and multiple winners. The game can be adapted for fewer than 8 players through the addition of Jokers as non-winning cards.

| Number of Players | Additional Jokers | Cards per Player |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0 | 26 |

| 5 | 1 | 21 |

| 6 | 4 | 18 |

| 7 | 1 | 15 |

| 8 | 0 | 13 |

Alternatively, some low-ranked cards may be removed to balance the hands, although both twos of clubs should be retained to ensure the possibility of an opening split lead. For six players, in particular, a sensible alternative would be to remove both twos of diamonds instead of adding Jokers, dealing seventeen cards to each player.