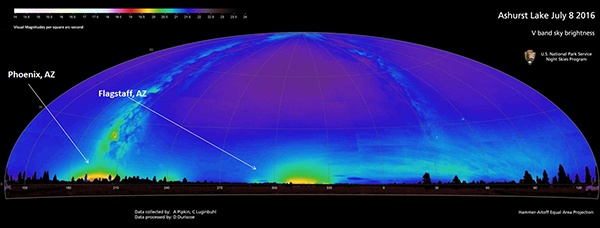

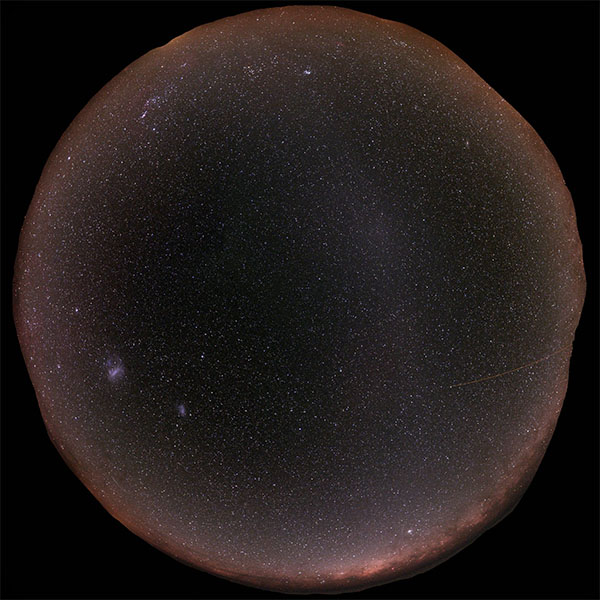

When our ancestors looked up into the night sky, they beheld the wonder of the stars. With our ubiquitous electrical lighting, many of us don’t see the same view today – our city skies are too bright from artificial light (previously discussed under Skyglow). We can see the brightest handful of stars, but most of us have forgotten how to navigate the night sky, recognising the constellations and other features such as the intricately structured band of the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds. There are features in the night sky other than stars (the moon, the planets, meteors, and comets), but we’re going to concentrate on the stars.

The Milky Way counts because it is made of stars. To our ancestors, it resembled a stream of milk flung across the night sky, a continuous band of brightness. But a small telescope reveals that it is made up of millions of faint stars, packed so closely that they blend together to our naked eyes. The Milky Way is our galaxy, a collection of roughly 100 billion stars and their planets.

The stars are apparently fixed in place with respect to one another. (Unlike the moon, planets, meteors, and comets, which move relative to the stars, thus distinguishing them.) The stars are not fixed in the sky relative to the Earth though. Each night, the stars wheel around in circles in the sky, moving over the hours as if stuck to the sky and the sky itself is rotating.

The stars move in their circles and come back to the same position in the sky approximately a day later. But not exactly a day later. The stars return to the same position after 23 hours, 56 minutes, and a little over 4 seconds, if you time it precisely. We measure our days by the sun, which appears to move through the sky in roughly the same way as the stars, but which moves more slowly, taking a full 24 hours (on average, over the course of a year) to return to the same position.

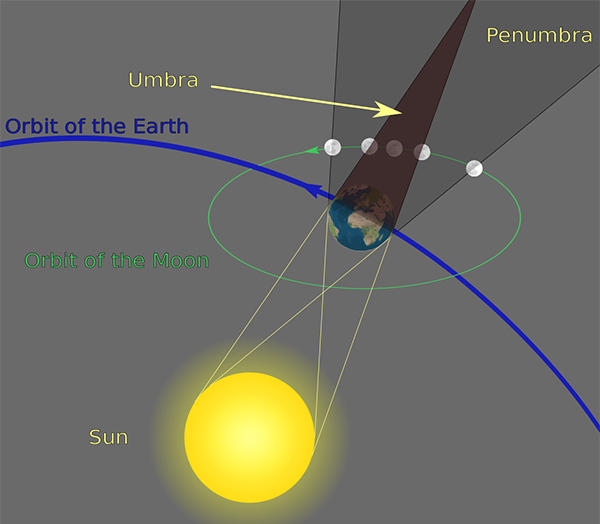

This difference is caused by the physical arrangement of the sun, Earth, and stars. Our Earth spins around on its axis once every 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 and a bit seconds. However in this time it has also moved in its orbit around the sun, by a distance of approximately one full orbit (which takes a year) divided by 365.24 (the average number of days in a year). This means that from the viewpoint of a person on Earth, the sun has moved a little bit relative to the stars, and it takes an extra (day/365.24) = 236 seconds for the Earth to rotate far enough for the sun to appear as though it has returned to the same position. This is why the solar day (the way we measure time with our clocks) is almost 4 minutes longer than the Earth’s rotation period (called the sidereal day, “sidereal” meaning “relative to the stars”).

Another way of looking at is that in one year the Earth spins on its axis 366.24 times, but in that same time the Earth has moved once around the sun, so only 365.24 solar days have passed. The sidereal day is thus 365.24/366.24 = 99.727% of the length of the solar day.

The consequence of all this is that slowly, throughout the year, the stars we see at night change. On 1 January, some stars are hidden directly behind the sun, and we can’t see them or nearby stars, because they are in the sky during the day, when their light is drowned out by the light of the sun. But six months later, the Earth is on the other side of its orbit, and those stars are now high in the sky at midnight and easily visible, whereas some of the stars that were visible in January are now in the sky at daytime and obscured.

This change in visibility of the stars over the course of a year applies mostly to stars above the equatorial regions. If we imagine the equator of the Earth extended directly upwards (a bit like the rings of Saturn) towards the stars, it defines a plane cutting the sky in half. This plane is called the celestial equator.

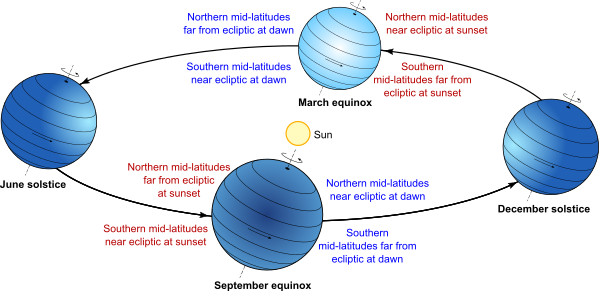

However the sun doesn’t move along this path. The Earth’s axis is tilted relative to its orbit by an angle of approximately 23.5°. So the sun’s apparent path through the sky moves up and down by ±23.5° over the course of a year, which is what causes our seasons. When the sun is higher in the sky it is summer, when it’s lower, it’s winter.

So as well as the celestial equator, there is another plane bisecting the sky, the plane that the sun appears to follow around the Earth – or equivalently, the plane of the Earth’s (and other planets’) orbit around the sun. This plane is called the ecliptic. It’s the stars along and close to the ecliptic that appear the closest to and thus the most obscured by the sun throughout the year.

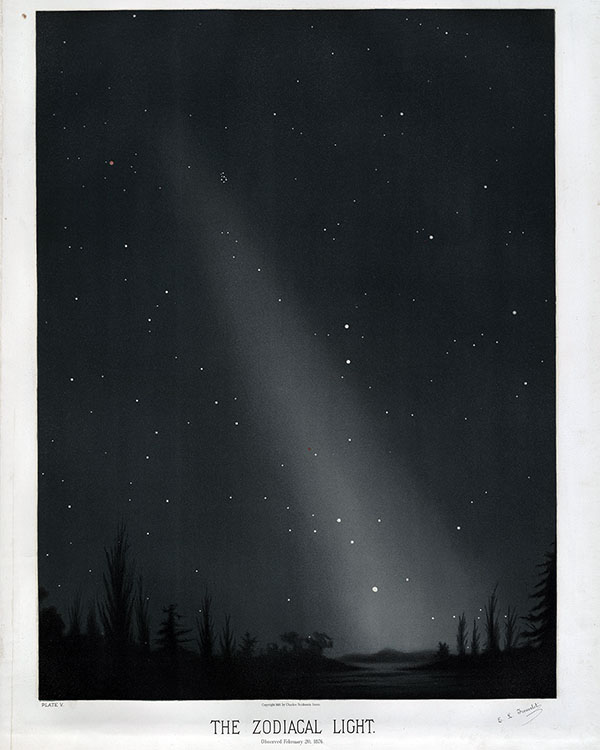

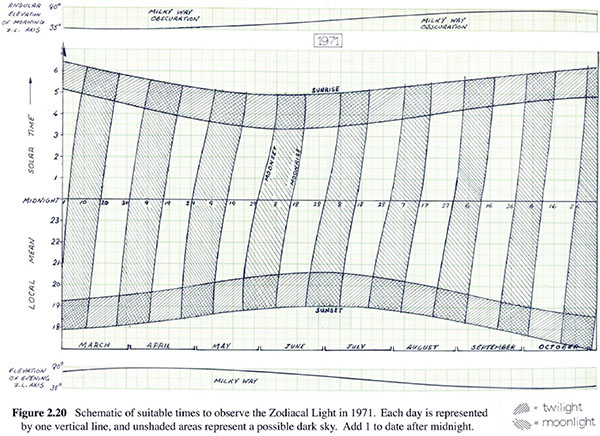

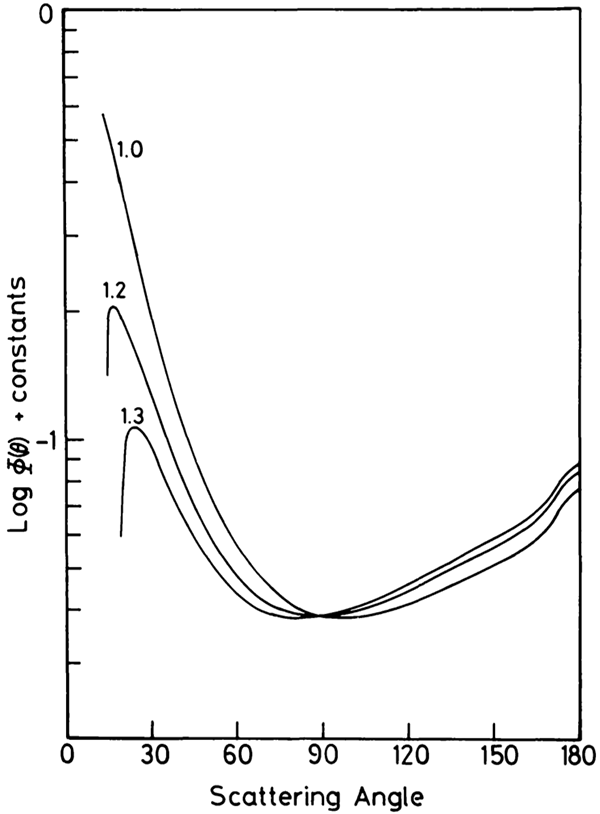

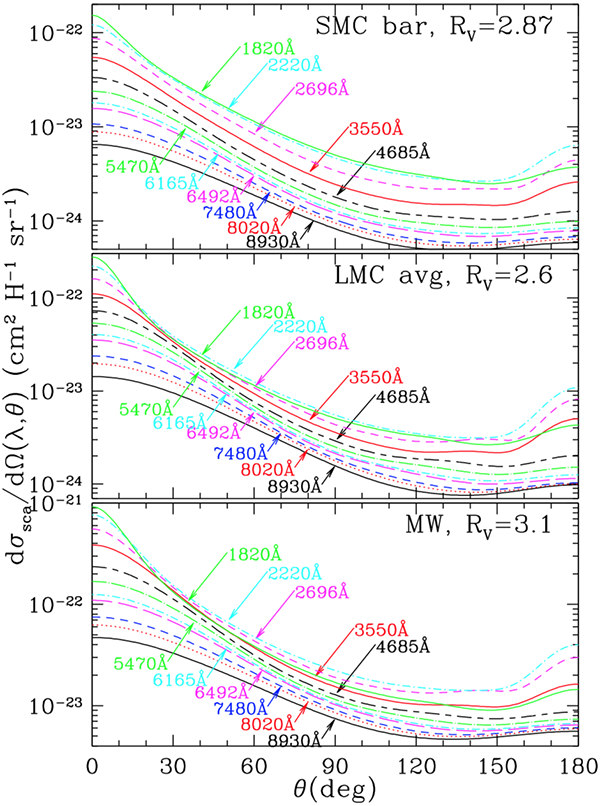

The constellations of the ecliptic have another name: the zodiac. We’ve met this term before as part of the name of the zodiacal light. The zodiacal light occurs in the plane of the planetary orbits, the ecliptic, which is the same as the plane of the zodiac. As an aside, the constellations of the zodiac include those familiar to people through the pre-scientific tradition of Western astrology: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius (“Scorpio” in astrology), Ophiuchus (ignored in astrology), Sagittarius, Capricornus (“Capricorn” in astrology), Aquarius, and Pisces. The system of astrology abstracts these real-world constellations into 12 idealised segments of the sky, each covering exactly 30° of the circle (in fact the constellations cover different amounts), and assigns portentous meanings to the positions of the sun, moon, and planets within each segment.

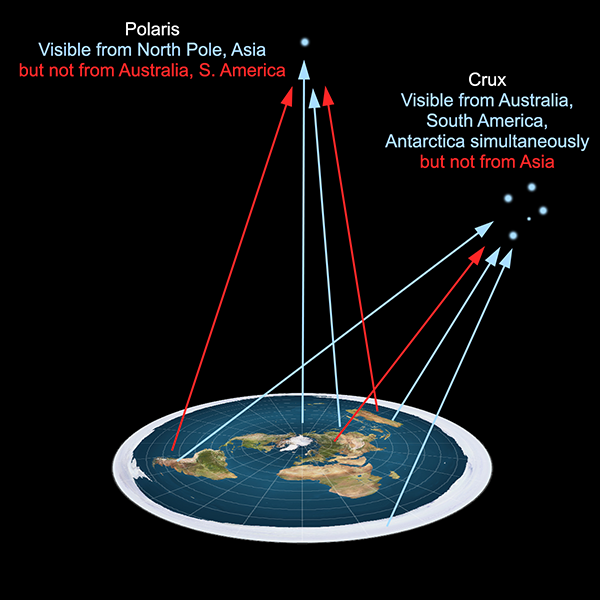

The stars close to the zodiac are completely obscured by the sun for part of the year, while the stars near the celestial equator appear close to the sun but might still be visible (with difficulty) immediately after sunset or before dawn. The stars far from these planes, however, are more easily visible throughout the whole year. The north star, Polaris, is almost directly above the North Pole, and it and stars nearby are visible from most of the northern hemisphere year-round. There is no equivalent “south pole star”, but the most southerly constellations—such as the recognisable Crux, or Southern Cross—are similarly visible year-round through most of the southern hemisphere.

Interestingly, Polaris is never visible from the southern hemisphere. Similarly, Crux is not visible from almost all of the northern hemisphere, except for a band close to the equator, from where it appears extremely low on the southern horizon. Crux is centred around 60° south, celestial latitude (usually known as declination), which means that it is below the horizon from all points north of latitude 30°N. (In practice, stars near the horizon are obscured by topography and the long path through the atmosphere, so it is difficult to spot Crux from anywhere north of about 20°N.)

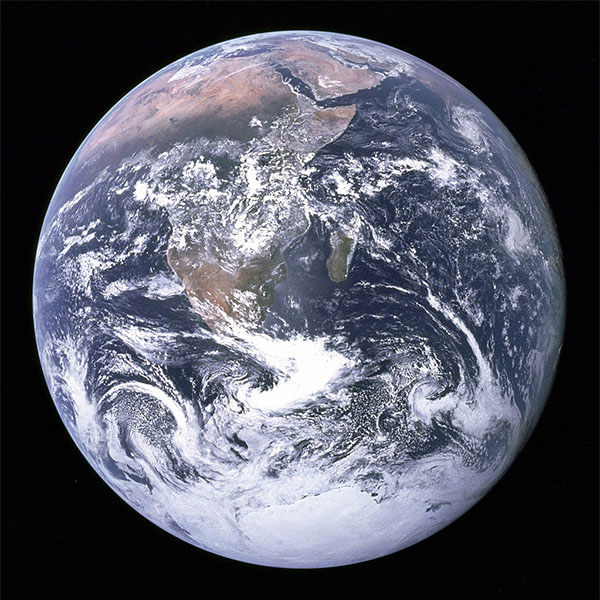

In general, stars at a given declination can never be seen from Earth latitudes 90° or more away, and only with difficulty from 80°-90° away. The reason is straightforward enough. From our spherical Earth, if you are standing at latitude x°N, all parts of the sky from (90-x)°S declination to the south celestial pole are below the horizon. And similarly if you’re at x°S, all parts of the sky from (90-x)°N declination to the north celestial pole are below the horizon. The Earth itself is in the way.

On the other hand, if you are standing at latitude x°N, all parts of the sky north of the same declination are visible every night of the year, while stars between x°N and (90-x)°S are visible only at certain times of the year.

With a spherical Earth, the geometry of the visibility of stars is readily understandable. On a flat Earth, however, there’s no obvious reason why some stars would be visible from some parts of the Earth and not others, let alone the details of how the visibilities change with latitude and throughout the year.

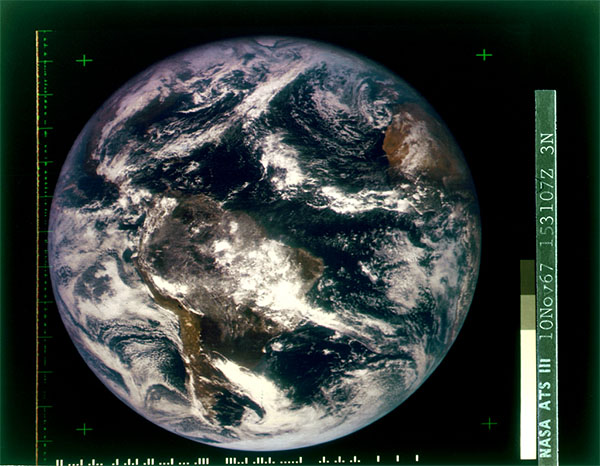

If we consider the usual flat Earth model, with the North Pole at the centre of a disc, and southern regions around the rim, it is difficult to imagine how Polaris can be seen from regions north of the equator but not south of it. And it is even more difficult to justify how it is even possible for southern stars such as those in Crux being visible from Australia, southern Africa, and South America but not from anywhere near the centre of the disc. The southern stars can be seen in the night sky from any two of these locations simultaneously, but if you use a radio telescope during daylight you can observe the same stars from all three at once. Things get even worse with Antarctica. In the southern winter, it is night at virtually every location in Antarctica at the same time, and many of the same stars are visible, yet cannot be seen from the northern hemisphere.

In any flat Earth model, there should be a direct line of sight from every location to any object above the plane of the Earth. To attempt to explain why there isn’t requires special pleading to contrived circumstances such as otherwise undetectable objects blocking lines of sight, or light rays bending or being dimmed in ways inconsistent with known physics.

The fact that when you look up at night, you can’t see all the stars visible from other parts of the Earth, is a simple consequence of the fact that the Earth is a globe.