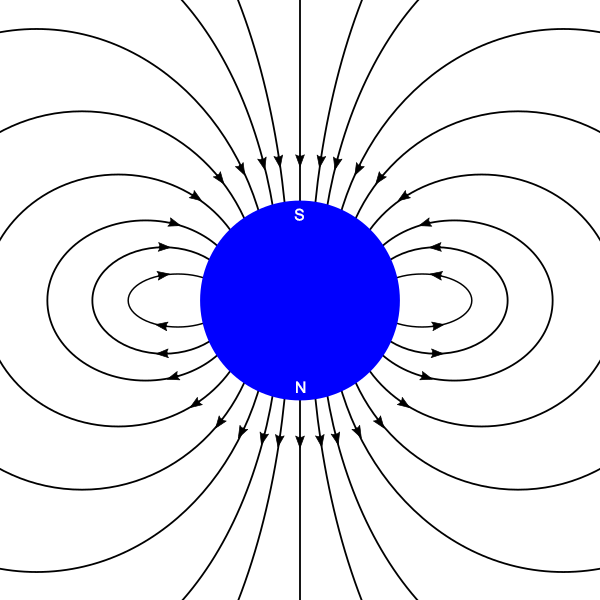

The theory of gravity is wildly successful in explaining and predicting the behaviours of masses. Isaac Newton’s formulation of gravity (published in his Principia Mathematica in 1686) is a simple formula that works very well for most circumstances of interest to people. When the gravitational potential energy or the velocity of a mass is very large, Albert Einstein’s general relativity (published 1915) is required to correctly determine behaviour. Newton’s gravity is in fact an approximation of general relativity that gives almost exactly the correct answer when the gravitational energy per unit mass is small compared to the speed of light squared, and the velocity is much smaller than the speed of light. For almost all calculation purposes, Newton’s law is sufficiently accurate to be used without worrying about the difference.

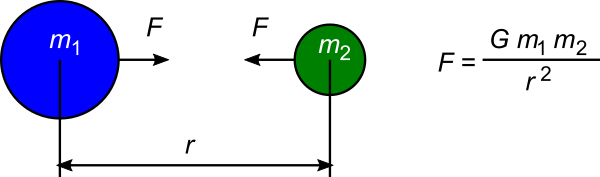

Newton’s law says that the force of gravitational attraction F between two bodies equals the universal gravitational constant G, multiplied by the masses of the two bodies m1 and m2, divided by the square of the distance r between them: F = G m1 m2/(r2).

Newton himself had no idea why this simple formula worked. Although he showed that it was accurate to the limits of the measurements available to him, he was deeply concerned about its philosophical implications. In particular, he couldn’t imagine how such a force could occur between two bodies separated by any appreciable distance or the vacuum of space. He wrote in a letter to Richard Bentley in 1692:

“That one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum without the mediation of anything else, by and through which their action and force may be conveyed from one another, is to me so great an absurdity that, I believe, no man who has in philosophic matters a competent faculty of thinking could ever fall into it.”

Newton was so concerned about this that he added an appendix to the second edition of the Principia – an essay titled the General Scholium. In this he wrote about the distinction between observational, experimental science, and the interpretation of observations (translated from the original Latin):

“I have not as yet been able to discover the reason for these properties of gravity from phenomena, and I do not feign hypotheses. For whatever is not deduced from the phenomena must be called a hypothesis; and hypotheses, whether metaphysical or physical, or based on occult qualities, or mechanical, have no place in experimental philosophy.”

In other words, Newton was being led by his observations to deduce physical laws and how the universe behaves. He refused to countenance speculation unsupported by evidence, and he accepted that the world behaved as observed, even if he didn’t like it. Commenting on Newton’s words in 1840, the philosopher William Whewell wrote:

“What is requisite is, that the hypotheses should be close to the facts, and not connected with them by other arbitrary and untried facts; and that the philosopher should be ready to resign it as soon as the facts refuse to confirm it.”

This affirms the position of a scientist as one who observes nature and tries to describe it as it is. Any hypothesis formed about how things are or why they behave the way they do must conform to all the known facts, and if any future observation contradicts the hypothesis, then the hypothesis must be abandoned (perhaps to be replaced with a different hypothesis). This is the scientific method in a nutshell, and guides our understanding of the shape of the Earth in these pages.

The universal gravitational constant G is a rather small number in familiar units: 6.674×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2. This means that the force of gravity between two everyday objects is so small as to be unnoticeable. For example, even large objects such as two 1-tonne cars a metre apart experience a gravitational force between them of only 6.674×10−5 newtons – far too small to move the cars against rolling friction, even with the brakes off. Also, the distance between the masses in Newton’s formula is the distance between the centres of mass of the objects, not the closest surfaces. The centres of mass of two cars can’t be brought closer together than about 2 metres in practice, even with the cars touching each other (unless you crush the cars).

Gravity really only starts to significantly affect things when you gather millions of tonnes of mass together. On Earth, the mass of the Earth (5.9722×1024 kilograms) itself dominates our experience with gravity. Removing mass 2 from Newton’s formula, we can calculate the acceleration a towards the centre of mass of the Earth, caused by the Earth’s gravity, as experienced at the surface of the planet (r = 6370 kilometres): a = G m1/(r2) = 6.674×10−11 × 5.9722×1024 / (6370×103)2 = 9.82 m/s2. This number matches experimental observations we can make of the gravity on the surface of the Earth (for example, using a pendulum: see also Airy’s coal pit experiment).

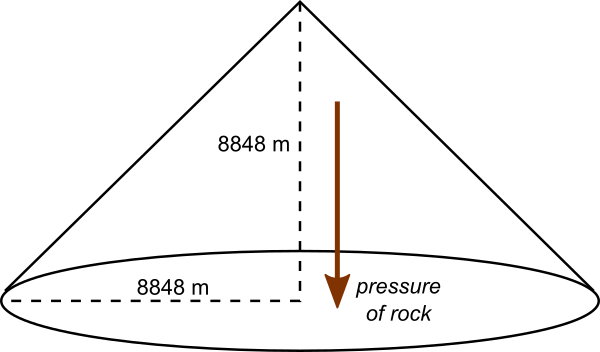

So large object like planets or other astronomical bodies experience a significant gravitational force on parts of themselves. Think about a tall mountain, such as Mount Everest. Let’s estimate the mass of Mount Everest – just roughly will do for our purposes. It is 8848 metres tall, above sea level. Let’s imagine it’s roughly a cone, with sides sloping at 45°. That makes the radius of the base 8848 metres, and its volume is π × 88483 / 3 = 7.25×1011 cubic metres. The density of granite is 2.75 tonnes per cubic metre, so the mass of Mount Everest is roughly 2×1015 kg. It experiences a gravitational force of approximately 2×1016 newtons, pulling it down towards the rest of the Earth.

Obviously Mount Everest is strong enough to withstand this enormous force without collapsing. But how much higher could a mountain be without collapsing under its own mass? The taller a mountain gets, the more force pulls it down, but the structural strength of the rock making up the mountain does not increase. At some point there is a limit. Our conical Mount Everest model spreads that mass over an area of π × 88482 square metres. This means the pressure of the rock above on this area is 2×1016 / (π × 88482) = 8×107 pascals, or 80 megapascals (Mpa). Now, the compressive strength of granite is about 200 MPa. We’re pretty close already! Not to mention that rock can also shear and deform plastically, so we probably don’t even need to get as high as 200 MPa before something bad (or spectacular, depending on your point of view!) happens. A mountain twice as high as Everest would almost certainly be unstable and collapse very quickly.

As mountains get pushed up by tectonic activity, their bases spread out under the pressure of the rock above, so that they can’t exceed the limit of the tallest possible mountain. In practice, it turns out that glaciation also has a significant effect on the maximum height of mountains on Earth, limiting them to something not much higher than Everest [1].

Now, compared to the size of the Earth, even a mountain as tall as Everest is pretty insignificant. It is barely a thousandth of the radius of the planet. It’s often said that if shrunk down to the same size, the Earth would be smoother than a billiard ball. In a sense, this is actually true! Billiard and snooker balls are specified to be 52.5 mm in diameter, with a tolerance of 0.05 mm [2]. That is just under a 500th of the radius, so it would be acceptable to have billiard balls for professional play that are twice as rough as the Earth – although in practice I suspect that billiard balls are manufactured smoother than the quoted tolerance.

So, there is a physical limit to the strength of rock that means that Earth can’t have any protruding lumps of any significant size compared to its radius. Similarly, any deep trenches can’t be too deep either, or else they’ll collapse and fill in due to the gravitational stress on the rock pulling it together. The Earth is spherical in shape (more or less) because of the inevitable interaction of gravity and the structural strength of rock. Any astronomical body above a certain size will also necessarily be close to spherical in shape. The size may vary depending on the materials making up the body: rock is stronger than ice, so icy worlds will necessarily be spherical at smaller sizes than rocky ones.

The phenomenon of large bodies assuming a spherical shape is known as hydrostatic equilibrium, referring to the fact that this is the shape assumed by any body with no resistance to shear forces, in other words fluids. For ice and rock, the resistance to shear force is overcome by gravity for objects of size a few hundred to a thousand or so kilometres in diameter. The asteroid Ceres is a hydrostatic spherical shape, with a diameter of 945 km. On the other hand, Saturn’s moon Iapetus is the largest known object to deviate significantly from hydrostatic equilibrium, with a diameter of 1470 km. Iapetus is almost spherical, but has an unusual ridge of mountains running around its equator, with a height around 20 km – about 1/36 of the moon’s radius.

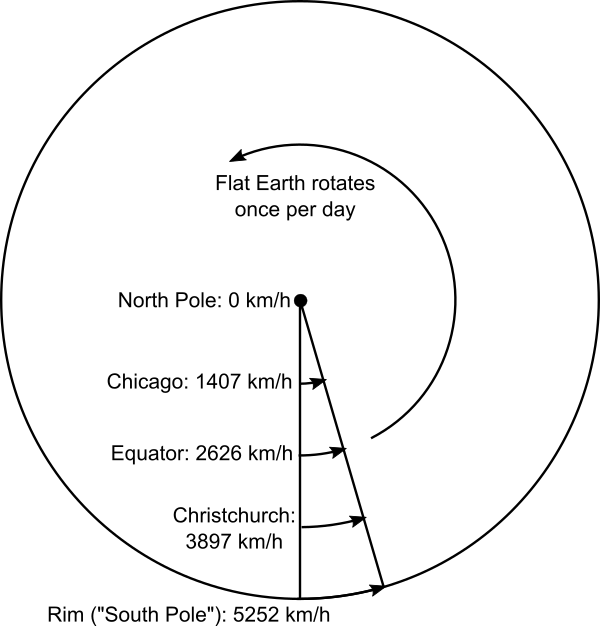

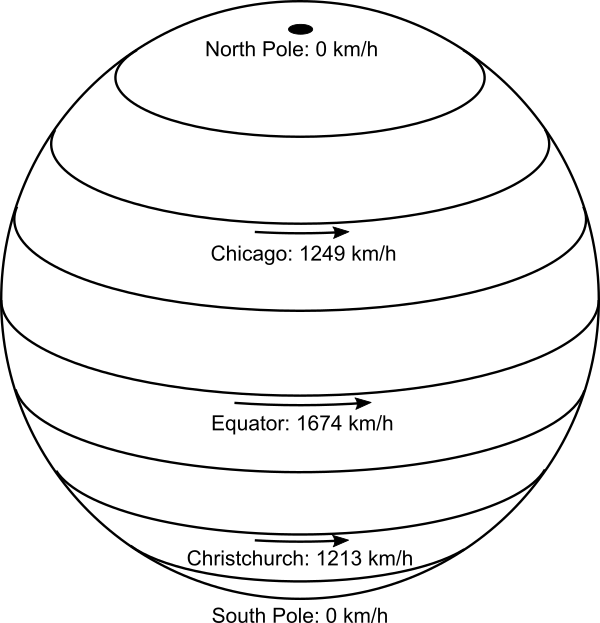

It’s safe to say, however, that any planetary sized object has to be very close to spherical – or spheroidal if rotating rapidly, causing a slight bulge around the equator due to centrifugal force. This is because of Newton’s law of gravity, and the structural strength of rock. Our Earth, naturally, is such a sphere.

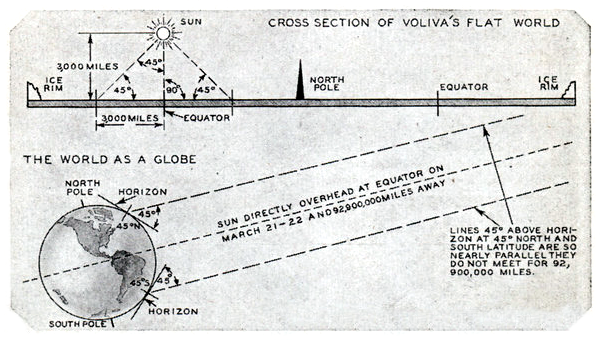

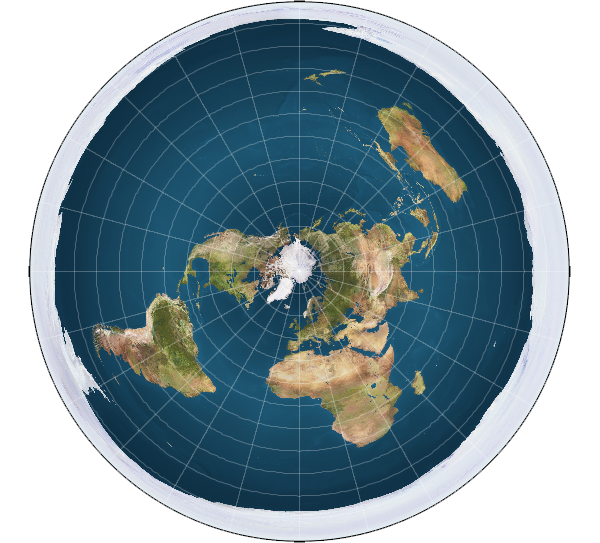

Flat Earth models must either conveniently ignore this conclusion of physics, or posit some otherwise unknown force that maintains the mass of the Earth in a flat, non-spherical shape. By doing so, they violate Newton’s principle that one must be guided by observation, and discard any hypothesis that does not fit the observed facts.

References:

[1] Mitchell, S. G., Humphries, E. E., “Glacial cirques and the relationship between equilibrium line altitudes and mountain range height”. Geology, 43, p. 35-38, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1130/G36180.1

[2] Archived from worldsnooker.com on archive.org: https://web.archive.org/web/20080801105033/http://www.worldsnooker.com/equipment.htm