Possibly the most obvious property of our sun is that it is visible from Earth during daylight hours, but not at night. The visibility of the sun is in fact what defines “day time” and “night time”. At any given time, the half of the Earth facing the sun has daylight, while the other half is in the shadow of the Earth itself, blocking the sun from view. It’s trivial to verify that parts of the Earth are in daylight at the same time as other parts are in night, by communicating with people around the world.

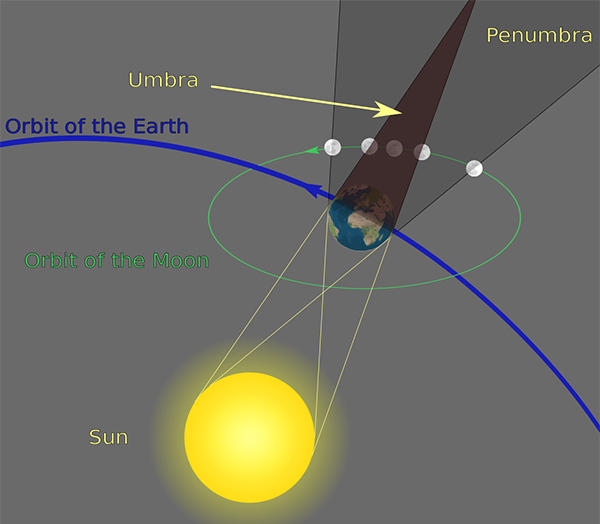

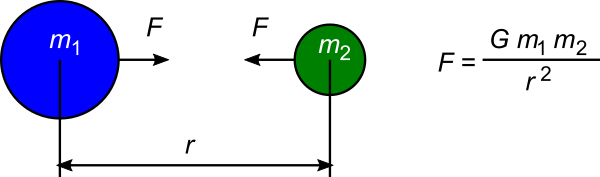

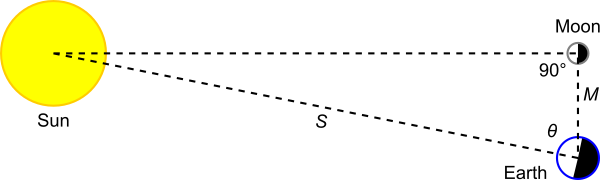

The first physical property of the sun to be measured was how far away it is. In the 3rd century BC, the ancient Greek Aristarchus of Samos (who we met briefly in 2. Eratosthenes’ measurement) developed a method to measure the distance to the sun in terms of the size of the Earth, using the geometry of the relative positions of the sun and moon. Firstly, when the moon appears exactly half-illuminated from a point on Earth, it means that the angle formed by the sun-moon-Earth is 90°. If you observe the angle between the sun and the moon at this time, you can determine the distance to the sun as a multiple of the distance to the moon.

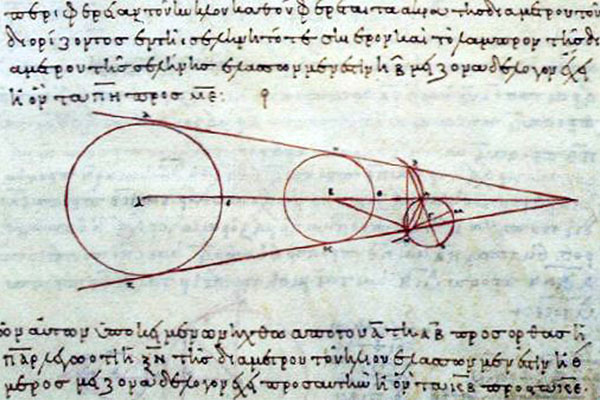

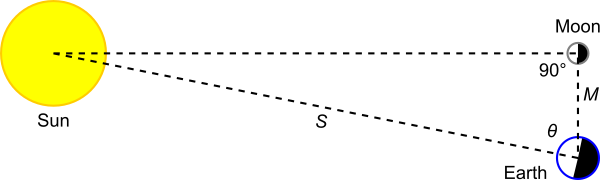

Geometry of the sun, moon, and Earth when the moon appears half-illuminated.

In the figure, if you measure the angle θ, then the ratio of the distance to the sun S divided by the distance to the moon M is the reciprocal of the cosine of θ. Aristarchus then used the size of the shadow of Earth on the moon during a lunar eclipse to obtain further equations relating the distances to the sun and moon and the size of the Earth.

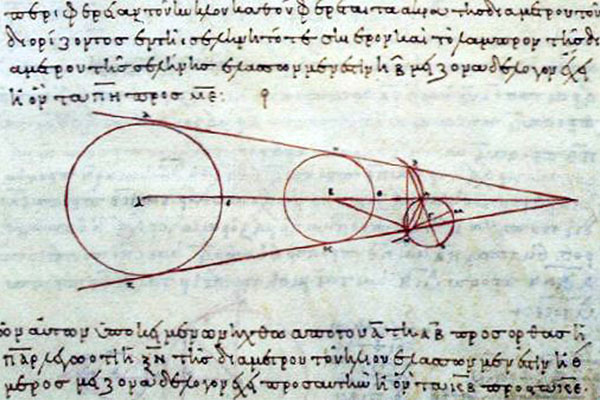

A medieval copy of Aristarchus’s drawing of the geometry of the sun-Earth-moon system during a lunar eclipse. (

Public domain image.)

By combining these results, you can calculate the distances to both the sun and the moon in terms of the radius of the Earth. Aristarchus got the wrong answer, estimating that the sun was only about 19 times further away than the moon, because of the limited precision of his naked eye angle measurements (it’s actually 390 times further away). But Eratosthenes later made more accurate measurements (which were again discussed in Eratosthenes’ measurement), most likely using the same method.

The first rigorous measurement of the absolute distance to the sun was made by Giovanni Cassini in 1672. By this time, observations of all the known celestial bodies in our solar system and some geometry had well and truly established the relative distances of all the orbits. For example, it was known that the orbital radius of Venus was 0.72 times that of Earth, while the orbit of Mars was 1.52 times that of Earth. To measure the absolute distance to the sun, Cassini used a two-step method, the first step of which was measuring the distance to the planet Mars. This is actually a lot easier to do than measuring the distance to the sun, because Mars can be seen at night, against the background of the stars.

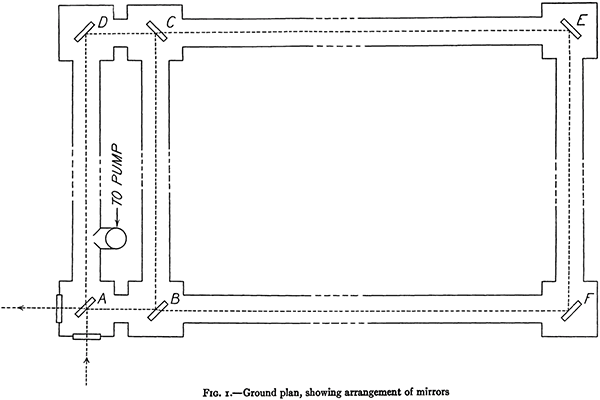

Cassini dispatched his colleague Jean Richer to Cayenne in French Guiana, South America, and the two of them arranged to make observations of Mars from there and Paris at the same time. By measuring the angles between Mars and nearby stars, they determined the parallax angle subtended by Mars across the distance between Paris and Cayenne. Simple geometry than gave the distance to Mars in conventional distance units. Then applying this to the relative distances to Mars and the sun gave the absolute distance from the Earth to the sun.

Since 1961, we’ve had a much more direct means of measuring solar system distances. By bouncing radar beams off the moon, Venus, or Mars and measuring the time taken for the signal to return at the speed of light, we can measure the distances to these bodies to high precision (a few hundred metres, although the distances to the planets change rapidly because of orbital motions) [1].

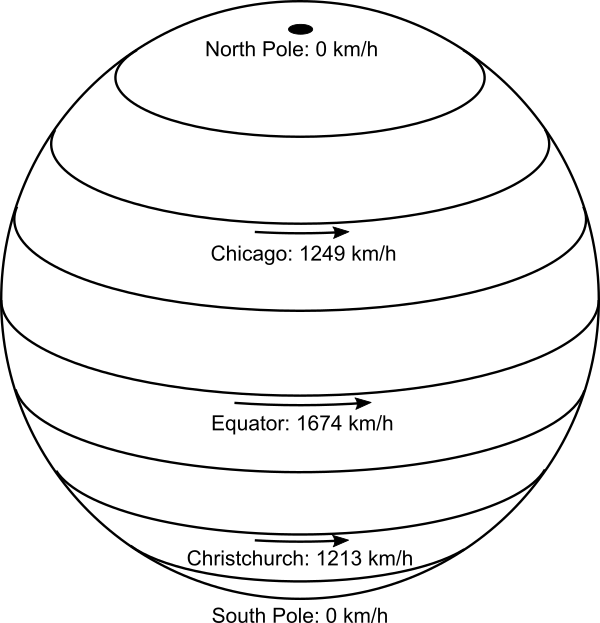

The Earth orbits the sun at a distance of approximately 150 million kilometres. Once we know this, we can work out the size of the sun. The angular size of the sun as seen from Earth can be measured accurately, and is 0.53°. Doing the mathematics, 0.53°×(π/180°)×150 = 1.4, so the sun is about 1.4 million kilometres in diameter, some 109 times the diameter of the Earth. This is the diameter of the visible surface – the sun has a vast “atmosphere” that we cannot see in visible light. Because of its vast distance compared to the size of the Earth, the sun’s angular size does not change appreciably as seen from different parts of the Earth. The difference in angular size between the sun directly overhead and on the horizon (roughly the Earth’s radius, 6370 km, further away) is only about 6370/150000000×(180°/π) = 0.002°.

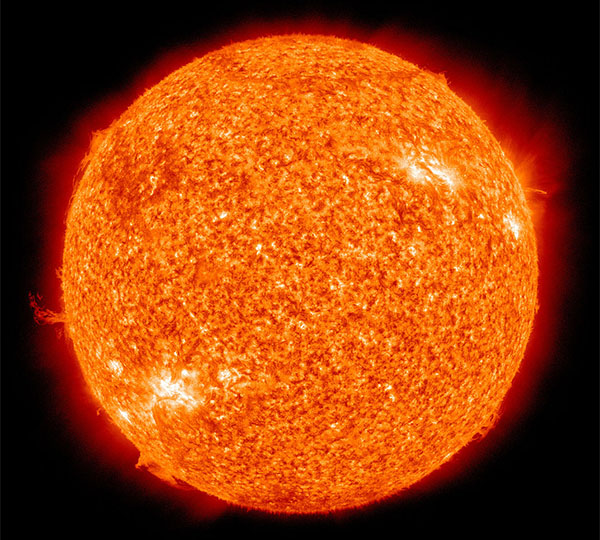

Our sun is, in fact, a star – a huge sphere composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. It produces energy from mass through well-understood processes of nuclear fusion, and conforms to the observed properties of stars of similar size. The sun appears much larger and brighter than stars, and heats the Earth a lot more than stars, because the other stars are all so much further away.

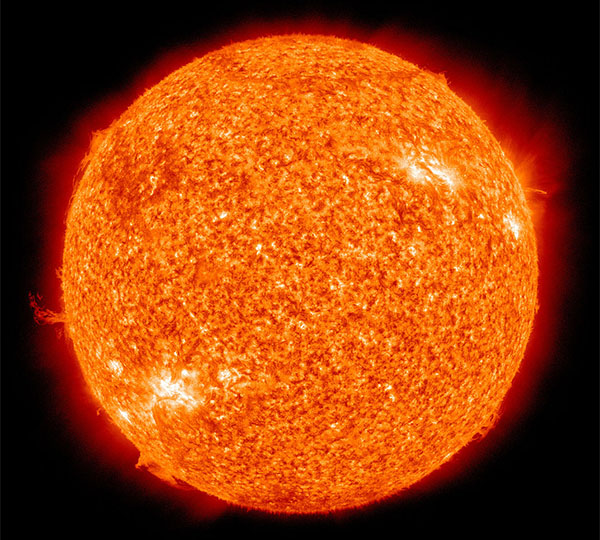

Our sun, observed in the ultraviolet as a false colour image by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory satellite. (

Public domain image by NASA.)

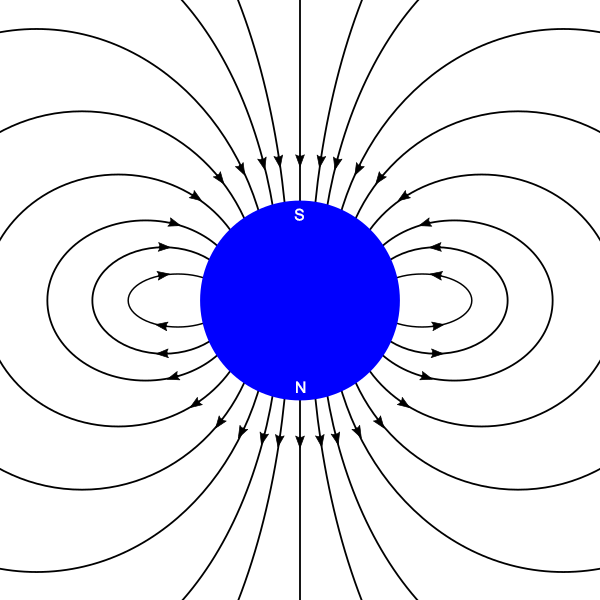

Like all normal stars, the sun radiates energy uniformly in all directions. This is expected from the models of its structure, and can be inferred from the uniformity of illumination across its visible disc. The fact that the sun’s polar regions are just as bright as the equatorial edges implies that the radiation we see in the ecliptic plane (the plane of Earth’s orbit) is reproduced in all directions out of the plane as well.

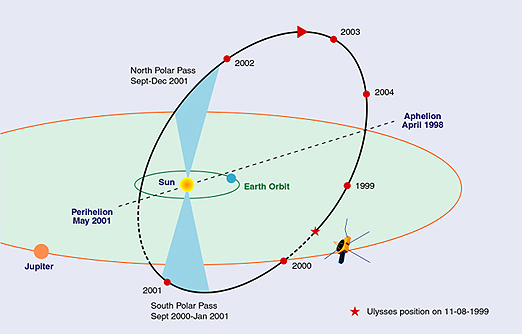

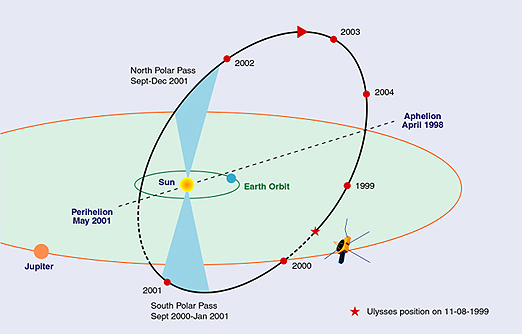

NASA’s Ulysses solar observation spacecraft was launched in 1990 and used a gravity slingshot assist from Jupiter to put it into a solar orbit inclined at about 80° to the ecliptic plane. This allowed it to directly observe the sun’s polar regions.

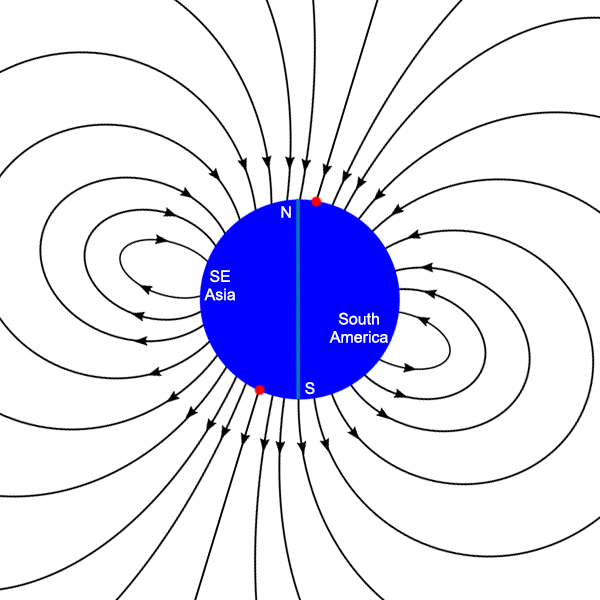

Polar orbit of

Ulysses around the sun, giving it views of both the sun’s north and south poles. (

Public Domain image by NASA.)

Now, I tried to find scientific papers using data from Ulysses to confirm that the sun indeed radiates electromagnetic energy (visible light, ultraviolet, etc.) uniformly in all directions. However, it seems that no researchers were willing to dedicate space in a paper to discussing whether the sun radiates in all directions or not. It’s a bit like looking for a research paper that provides data on whether apples fall to the ground or not. What I did find are papers that use data from Ulysses’ solar wind particle flux detectors to measure if the energy emitted by the sun as high energy particles varies with direction.

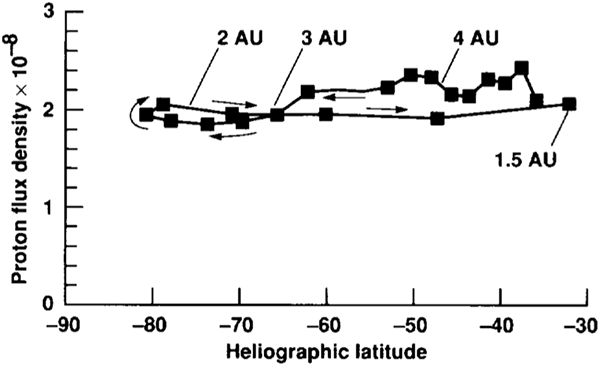

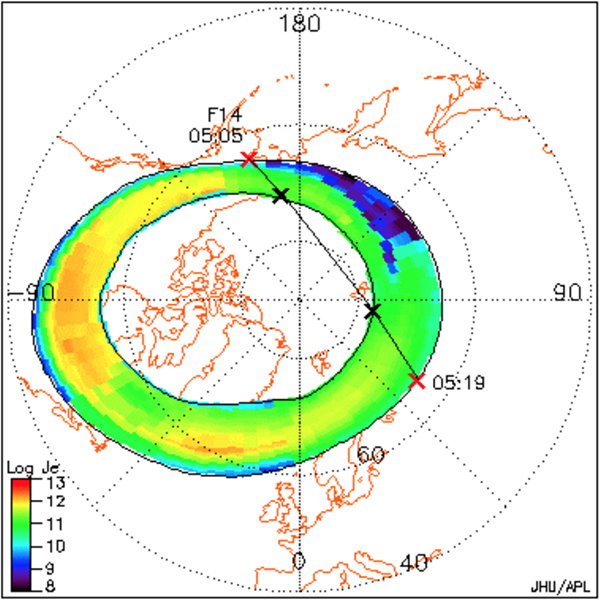

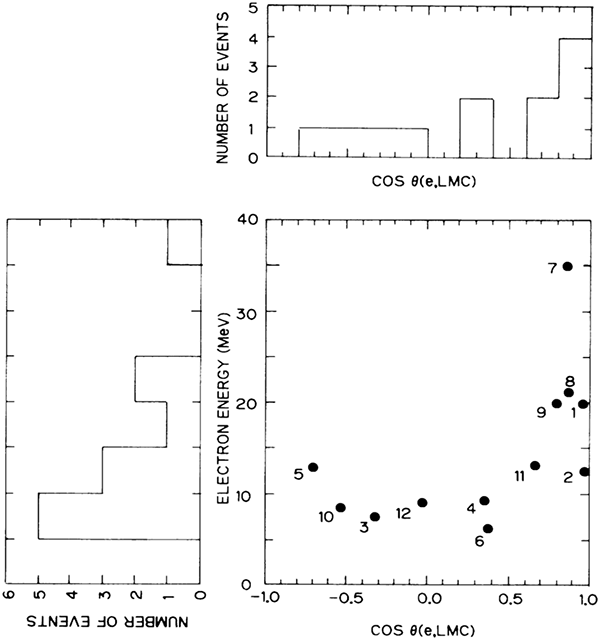

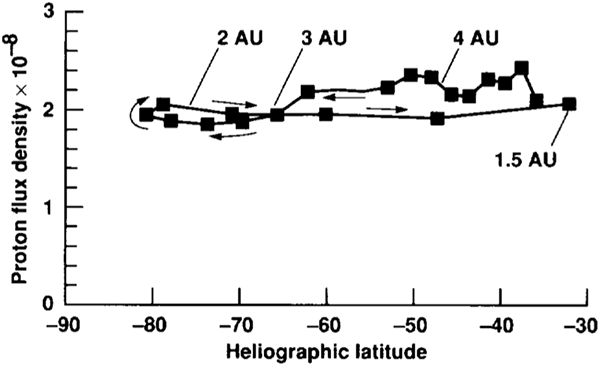

Proton flux density observed by Ulysses at various heliographic (sun-centred) latitudes. -90 is directly south of the sun, 0 would be in the ecliptic plane. The track shows Ulysses’ orbit, changing in distance and latitude as it passes under the sun’s south polar regions. Figure reproduced from [2].

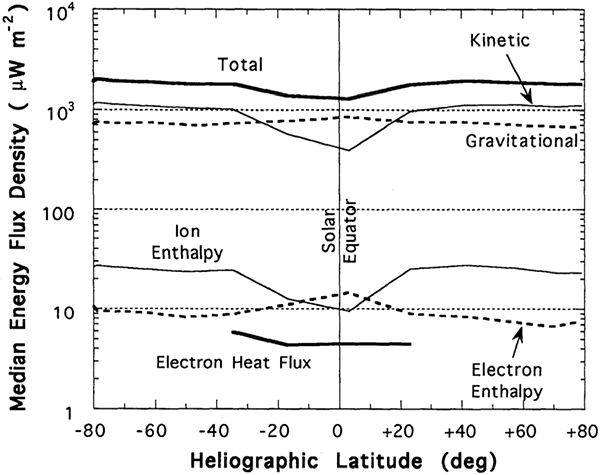

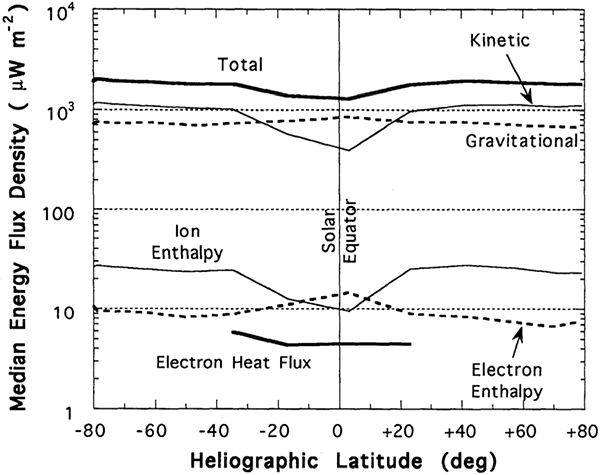

Various solar wind plasma component energy fluxes observed by Ulysses at various heliographic latitudes. Figure reproduced from [3].

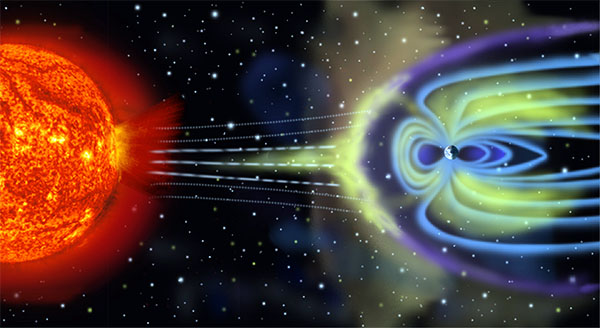

As these figures show, the energy emitted by the sun as solar wind particles is pretty constant in all directions, from equatorial to polar. Interestingly, there is a variation in the solar wind energy flux with latitude: the solar wind is slower and less energetic close to the plane of the ecliptic than at higher latitudes. The solar wind, unlike the electromagnetic radiation from the sun, is affected by the structure of the interplanetary medium. The denser interplanetary medium in the plane of the ecliptic slows the wind. The amount of slowing provides important constraints on the physics of how the solar wind particles are accelerated in the first place.

Anyway, given there are papers on the variation of solar wind with direction, you can bet your bottom dollar that there would be hundreds of papers about the variation of electromagnetic radiation with direction, if it had been observed, because it goes completely counter to our understanding of how the sun works. The fact that the sun radiates uniformly in all directions is such a straightforward consequence of our knowledge of physics that it’s not even worth writing a paper confirming it.

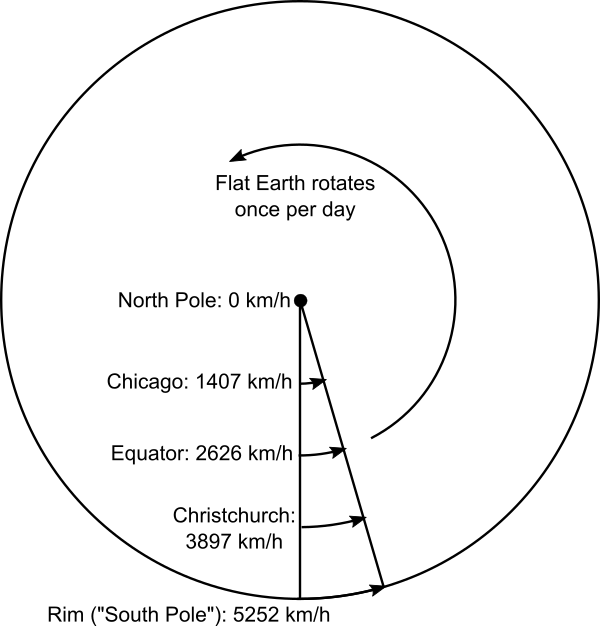

Now, in our spherical Earth model, all of the above observations are both consistent and easily explicable. In a Flat Earth model, however, these observations are less easily explained.

Why is the sun visible in the sky from part of the Earth (during daylight hours), while in other parts of the Earth at the same time it is not visible (and is night time)?

The most frequently proposed solution for this is that the sun moves in a circular path above the disc of the Flat Earth, shining downwards with a sort of spotlight effect, so that it only illuminates part of the disc. Although there is a straight line view from areas of night towards the position of the sun in the sky, the sun does not shine in that direction.

Given that we know the sun radiates uniformly in all directions, we know this cannot be so. Furthermore, if the sun were a directional spotlight, how would such a thing even come to be? Directional light sources do occur in nature. They are produced by synchrotron radiation from a rapidly rotating object: for example, a pulsar. But pulsars rotate and sweep their directional beams through space on a timescale of approximately one second. If our sun were producing synchrotron radiation, its spotlight beam would be oscillating many times per minute – something which is not observed.

Even furthermore, if the sun is directional and always above the plane of the Flat Earth, it should be visible in the night sky, as an obscuration passing in front of the stars. This prediction of the Flat Earth model is not seen – it is easy to show that no object the size of the sun obscures any stars at night.

And yet furthermore, if the sun is directional, there are substantial difficulties in having it illuminate the moon. Some Flat Earth models acknowledge this and posit that the moon is self-luminous, and changes in phase are caused by the moon itself, not reflection of sunlight. This can easily be observed not to be the case, since (a) there are dark shadows on the moon caused by the light coming from the location of the sun in space, and (b) the moon darkens dramatically during lunar eclipses, when it is not illuminated by the sun.

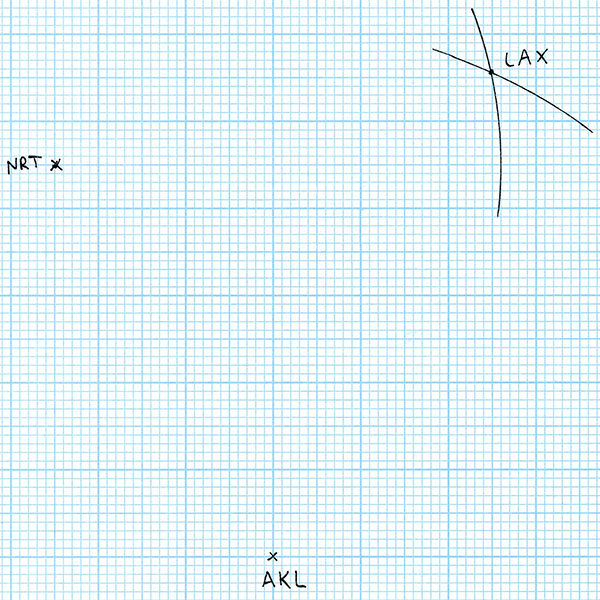

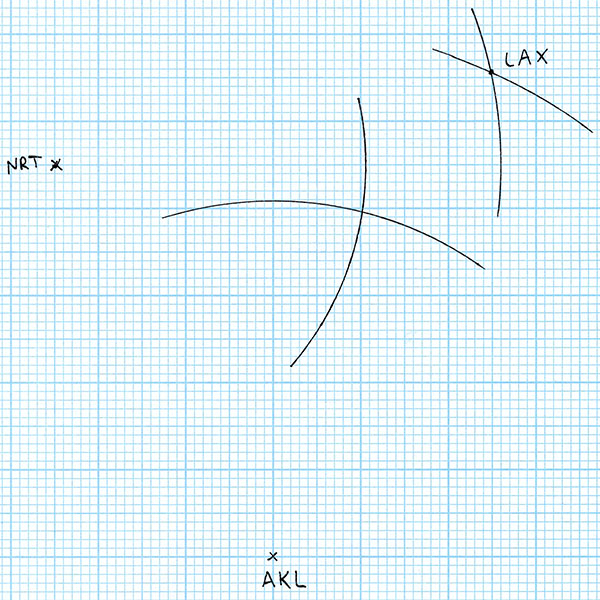

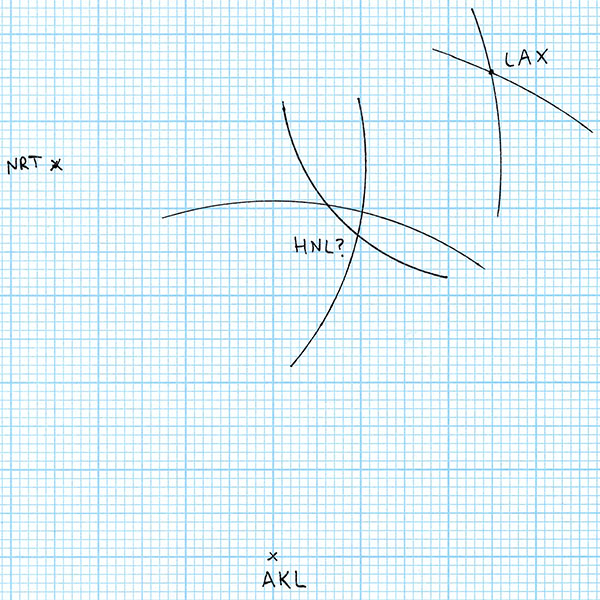

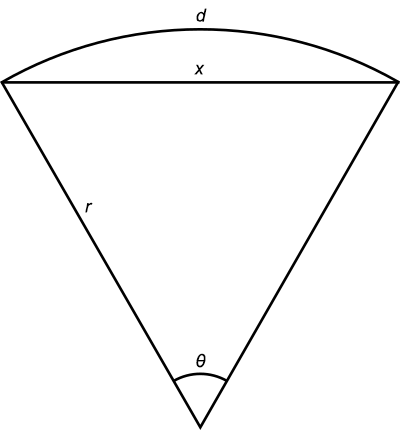

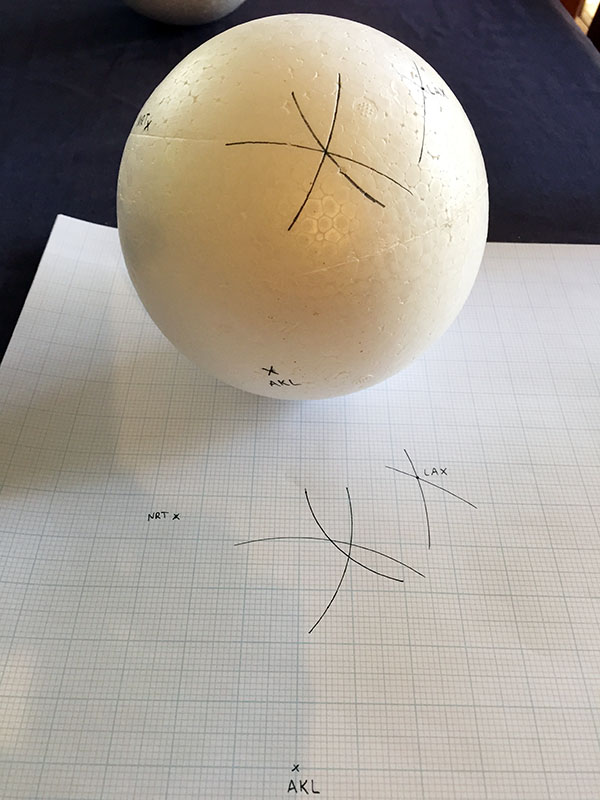

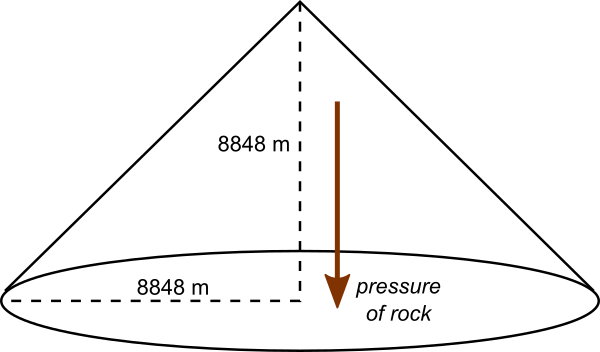

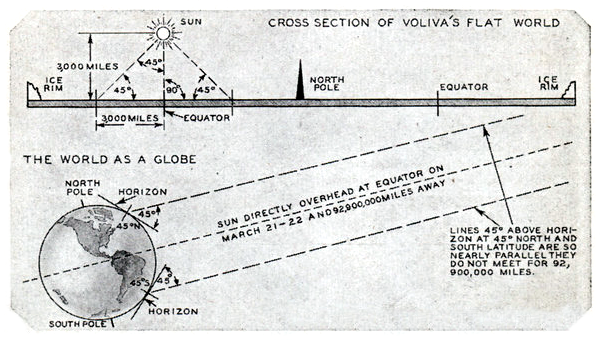

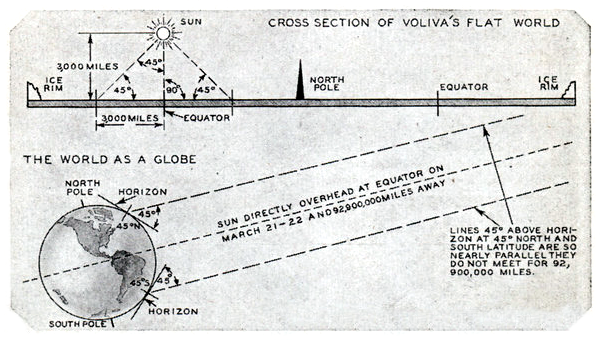

In addition to the directional spotlight effect, typical Flat Earth models state that the distance to the sun is significantly less than 150 million kilometres. Flat Earth proponent Wilbur Glenn Voliva used geometry to calculate that the sun must be approximately 3000 miles above the surface of the Earth to reproduce the zenith angles of the sun seen in the sky from the equator and latitudes 45° north and south.

Wilbur Glenn Voliva’s calculation that the sun is 3000 miles above the Flat Earth. Reproduced from Modern Mechanics, October 1931, p. 73.

Aside from the fact that Voliva’s distance does not give the correct zenith angles for any other latitudes, it also implies that the sun is only about 32 miles in diameter, given the angular size seen when it is overhead, and that the angular size of the sun should vary significantly, becoming only 0.53°/sqrt(2) = 0.37° when at a zenith angle of 45°. If the sun is this small, there are no known mechanisms than can supply the energy output it produces. And the prediction that the sun would change in angular size is easily disproved by observation.

The simplest and most consistent way of explaining the physical properties of our sun is in a model in which the Earth is a globe.

References:

[1] Muhleman, D. O., Holdridge, D. B., Block, N. “The astronomical unit determined by radar reflections from Venus”. The Astrophysical Journal, 67, p. 191-203, 1962. https://doi.org/10.1086/108693

[2] Barnes, A., Gazis, P. R., Phillips, J. L. “Constraints on solar wind acceleration mechanisms from Ulysses plasma observations: The first polar pass”. Geophysical Research Letters, 22, p. 3309-3311, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1029/95GL03532

[3] Phillips, J. L., Bame, S. J., Barnes, A., Barraclough, B. L., Feldman, W. C., Goldstein, B. E., Gosling, J. T., Hoogeveen, G. W., McComas, D. J., Neugebauer, M., Suess, S. T. “Ulysses solar wind plasma observations from pole to pole”. Geophysical Research Letters, 22, p. 3301-3304, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1029/95GL03094